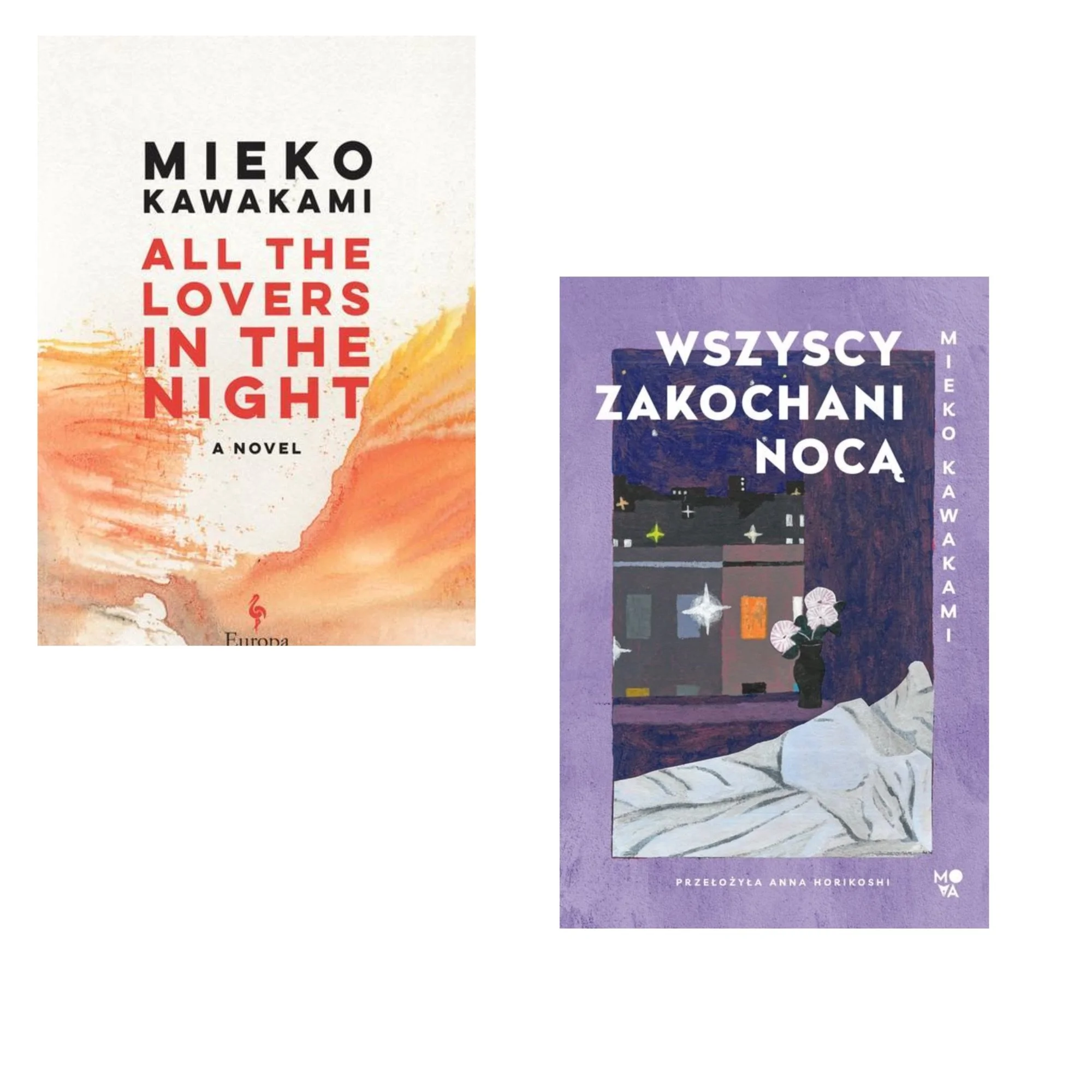

All the Lovers in the Night by Mieko Kawakami

The manuscript inside was six hundred pages long, so Hijiri’s hands bent under its weight.

(..) Can you believe someone had that much to say to other people?”

“In this sense, trust is not so important. It can burst like a bubble. But ‘relying on someone’ is something else, at least for me. Yes, ‘relying’ and ‘trusting’ are two different things. If I rely on someone, it’s like giving them a part of myself.”

At first glance, you might say this is a novel about the female experience in Japanese society. But for me, it felt much broader—these themes, these expectations, they exist everywhere. In many ways, it reminded me of the reality in Poland.

Our main character, Fuyuko Irie, is a proofreader in her mid-thirties, someone who has always followed the rules. University, then a stable job, good insurance—the perfect, responsible path. And yet, as we get to know her, we see that despite liking her work and being deeply committed to it, she is completely detached from life. She is methodical, precise, making sure every book she proofreads is flawless, but her role is that of an observer, never allowing herself to engage.

She describes her work:

“I kept a cheat sheet ready with a diagram on which I had drawn the relationships between the characters, a timeline, and a plot summary, so that I could iron out the contradictions in the statements of individual characters. I even drew a plan of the residence that was the setting of the action.”

But she is not reading the way we do:

“Real reading must be avoided, but of course, I have to know the whole plot, all the time connections and so on, so I read very carefully, but so as not to get involved, not to feel anything. I focus only on spotting errors and inconsistencies in the text.”

As someone who loves books, I found this fascinating. It made me appreciate how much unseen labor goes into making books seamless for readers. But it also made me think about how often we live the way Fuyuko works—meticulously going through the motions, ensuring perfection, but never actually feeling.

Loneliness and a New Friendship

Fuyuko is terrible at social interactions, and her workplace is hostile, filled with bullying and exclusion. That’s why, when she reconnects with her former coworker, Hijiri, it feels like a turning point. Hijiri is everything Fuyuko is not—strong, independent, and unapologetic. She convinces Fuyuko to leave her toxic office job and start freelancing, giving her the freedom to escape a system that was suffocating her.

From their first conversation, I knew Hijiri would be my favorite. She sees the world in a way that’s refreshingly direct, yet unexpectedly warm. She explains why she wants to work with Fuyuko in a way that stuck with me:

“In this sense, trust is not so important. It can burst like a bubble. But ‘relying on someone’ is something else, at least for me. Yes, ‘relying’ and ‘trusting’ are two different things. If I rely on someone, it’s like giving them a part of myself.”

Their friendship is one of the strongest aspects of the book. It explores two very different types of loneliness: Fuyuko, who isolates herself completely, and Hijiri, who is fiercely independent but still not free.

Hijiri’s philosophy is simple:

“I’m one of those people who have to do everything my way. (…) That’s the best way. Do what you want, the way you want.”

And yet, even she is not exempt from societal pressure. Both of them, in their own ways, are constantly being judged and pushed into roles they don’t want—because that’s what society expects from women.

Hijiri reflects:

“If I told them that, they’d start: ‘But no one lives in the world alone, that’s not possible.’ I know that perfectly well, and that’s why I try to live the way I want, whenever I can.”

The Moment That Stuck With Me

One of the most striking scenes for me was when Hijiri talked about a trip she took with a guy. They were riding an elephant, and she noticed the elephant was bleeding, still being forced to work. She admitted that it made her sick. But she didn’t stop it. She didn’t say anything.

That moment stuck with me. Why didn’t she get off? Why didn’t she say, “That’s it, I’m done, I won’t be part of this”?

And then it hit me: we all participate, even when we know something is wrong. Silence and inaction are a kind of crime too. Maybe that’s why Hijiri doesn’t try to justify herself. She knows.

Later in the book, we see how she operates in a male-dominated world. She is sharp, observant, and refuses to be taken advantage of. She plays the game, but on her own terms. And yet, she is still judged. Her colleagues assume she sleeps around, that she’s “one of those women,” simply because she refuses to follow the expected path—settle down, get married, live quietly.

Fuyuko and the Search for Love

Fuyuko’s life shifts when she meets a man, and she begins to wonder what love actually is. Is it worth it to be with someone? To marry, to conform, just to avoid being alone?

Her married friends paint a bleak picture:

“It seems like this is the natural order of things, but I am terrified that I am only a mother and my husband is only a father and nothing more awaits us in life. (…) My husband and I will be left alone at home. We have nothing to talk about.”

The idea of a life that shrinks into a routine of obligation, where even love itself is worn down into habit, is terrifying. And yet, isn’t this what society keeps pushing women toward?

The Loneliness of Modern Life

For me, one of the most powerful moments in the book was about the loneliness we all live with—the things we don’t share, the burdens we carry alone, because we don’t want to be a burden on others.

*“I didn’t tell anyone that Mai was cheating on me. (..) Not Yoshii, not any of the other moms, not the friends I’m closer to. You’re the first.

• Really?

• Yeah, I don’t know why I confided in you.

Probably because you’re not in my life every day.”

There’s something so raw in that. We don’t want to overshare. We don’t want to make someone else responsible for our pain. Or maybe, deep down, we just don’t want a witness to our failures.

Final Thoughts

I won’t spoil too much of the story, but just know—this is not a Disney fairytale. And that’s exactly why it’s worth reading.

For me, All the Lovers in the Night is, above all, a story about women’s friendships and what it means to live consciously. It’s about questioning the roles we’ve been assigned, about loneliness, about how easy it is to slip into a passive existence where we avoid big decisions just to avoid failure.

As Fuyuko reflects:

“No, that was an excuse, I thought. I followed orders so diligently just to convince myself that I was doing something. But in reality, I was doing nothing. Nothing that would change my life. I didn’t want to think about it, I looked away. I was so afraid of failure that I preferred to do nothing. To make no significant decisions, just to avoid suffering if things didn’t work out.”

This book isn’t just about Fuyuko’s life—it’s about all of us who have ever hesitated, who have ever chosen the safe path instead of the one we actually wanted. And that, to me, is what makes it so powerful.

P.S. I absolutely love this quote from the book:

“The manuscript inside was six hundred pages long, so Hijiri’s hands bent under its weight.

(..) Can you believe someone had that much to say to other people?”

This really stuck with me because wow, that’s so true! Every book is someone’s story, someone’s thoughts that they felt were important enough to share. It’s easy to forget, but behind every book is a person who believed in those words enough to put them out into the world. And that, in itself, is something special.