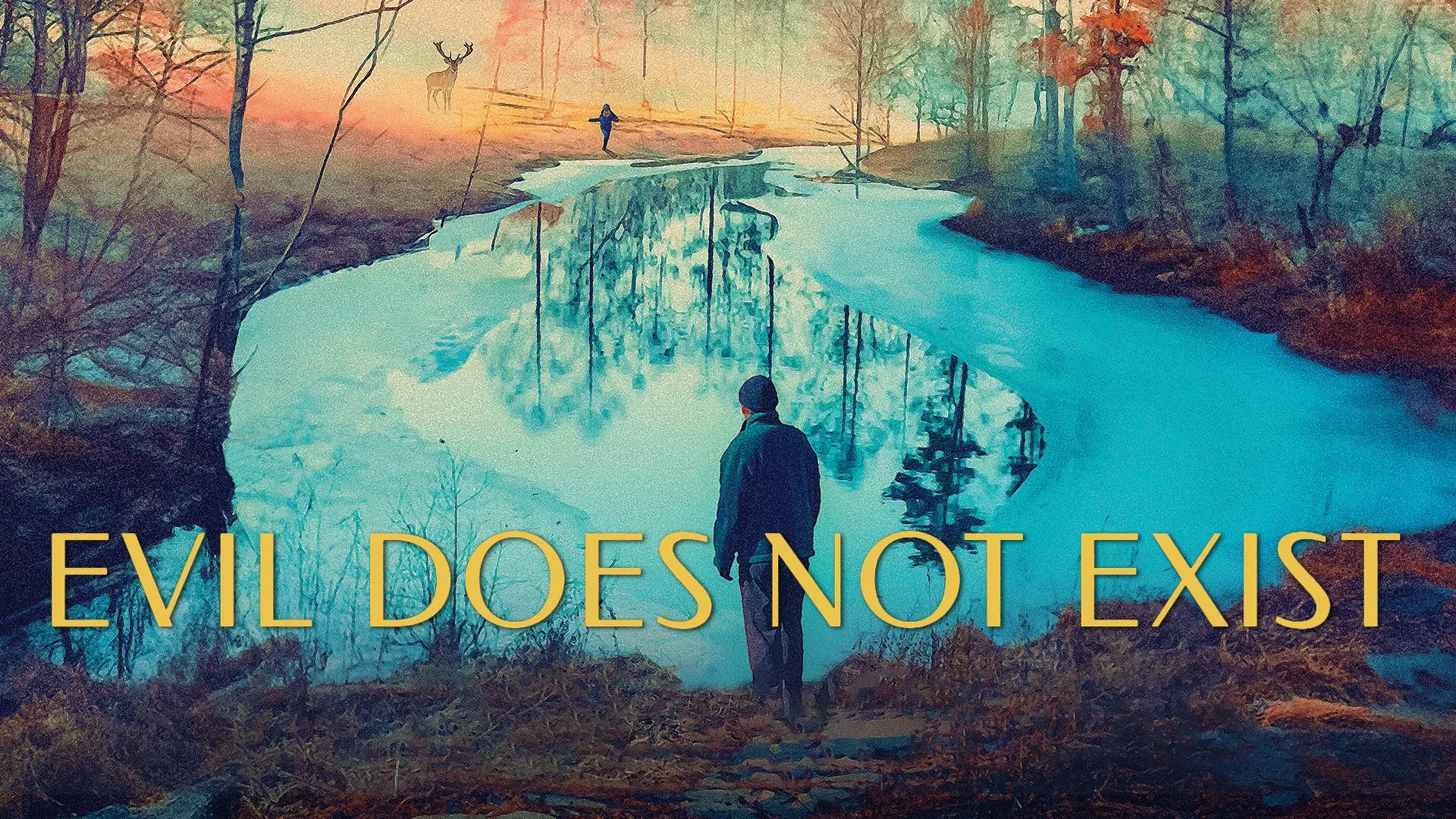

Evil Does Not Exist – My Review

This story showcases how greed blinds us and makes us forget about the impact of our decisions. It follows a company with no experience in development, funded by “Covid relief funds,” planning to build a glamping site in the middle of a peaceful village that deeply values nature and community.

The movie portrays how companies pretend to listen and care about locals’ opinions through consulting-style presentations and polished sales pitches. However, these efforts are hollow, as they fail to provide genuine answers or truly listen. Director Ryûsuke Hamaguchi goes further to reveal the performative nature of these interactions, showing that the people sent to conduct the meetings are merely hired actors and nurses—individuals with no real background—paid low wages to present the façade of engagement while the company chases government funding.

One of my favorite elements was the depiction of the Japanese community and the challenges of truly integrating into it. When the company is supposedly listening to locals, Schachi Minemura steps in, admitting that she’s not originally from the village. She moved from Tokyo to serve soba, drawn by the area’s extraordinarily clear water. Despite not being a local, she tries to advocate for the community, acknowledging her place as an outsider. This resonated with me deeply—if you’ve ever been to Japan, you might know that being fully accepted as one of them is nearly impossible. It’s both sad and beautiful.

Another striking moment is when the village headman explains their philosophy: every action has an impact. They live carefully to ensure they don’t harm neighboring villages, emphasizing that balance is key. This way of life contrasts sharply with the company’s greed-driven actions. It’s a reminder that whatever we do should be driven by consciousness and necessity, not by greed.

As the story unfolds, the director of the company reveals his true colors, telling the hired nurse and actor to “make it happen, whatever it takes.” This cold, dismissive attitude shocked me—it felt eerily American, with its “cost doesn’t matter” ethos. Their strategy includes seducing the village handyman, the protagonist, who knows everything about the area and has a young daughter.

The handyman reluctantly agrees to meet with the salespeople, who try every trick to win him over. The actor, posing as someone interested in working as a guard at the glamping site, tries to persuade the handyman by claiming he wants to learn from him. Of course, we know it’s all a lie. This showcases how people from big cities often lose their moral compass in their relentless pursuit of success, driven by greed rather than conscience.

Despite their efforts, the handyman remains unconvinced and takes them on a journey to show them what life in the village is like—cutting firewood, fetching water from the river, and more. During one pivotal moment, he mentions that the glamping site is located on a deer migration route. When asked if deer attack people, he replies that they don’t—unless a fawn is harmed. Then, the parent will retaliate. This seems like a metaphor: the villagers, like the deer, are peaceful and prefer not to engage with outsiders (as symbolized by the soba lady). But when threatened, they will fight back.

And he does fight back.

The ending left me puzzled—it’s unclear what exactly happened. But perhaps that’s the point. In the final moments, we see his daughter, hurt and in pain, and a deer with its baby that has been shot. This imagery feels deeply symbolic, mirroring the earlier metaphor about the peacefulness of the deer and the villagers, who only retaliate when threatened. It’s a powerful moment that lingers, leaving much unsaid and open to interpretation.

It made me realize how accustomed we’ve become to being spoon-fed tidy, well-defined narratives that don’t require us to think. Here, Hamaguchi challenges us to engage with the story and draw our own conclusions. He says “I think the ending is open to interpretation, and I welcome diverse perspectives on its meaning.”